My friend, let’s take it slow because the saint is made of clay! You can’t judge a heart by a face. Where did you get that certainty from? What if he was inoculated with Liberation Theology but hasn’t yet developed visible symptoms? It could be a typical case of an asymptomatic follower. And what if the symptoms show up in due time?

Liberation Theology was a movement that arose within the Catholic Church, born in Latin America, and had its most intense moments in the 1960s and 1970s. It sought to interpret the Christian faith from the reality of the poor and oppressed, defending that the Church should engage in the struggle against social, economic, and political injustices, focusing on the liberation of the marginalized.

The theology proposes that salvation is not only spiritual but also involves social transformation, promoting justice, peace, and equality. Inspired by the teachings of Jesus and a critical analysis of power structures, Liberation Theology seeks a more just and fraternal society.

My friend has reason to be worried — according to her vision of the Church, of course! — after all, Peru is the land of Father Gustavo Gutiérrez Merino Díaz (June 8, 1928 – October 22, 2024), theologian, philosopher, Dominican priest, and central figure of Liberation Theology. Gutiérrez taught at universities such as Notre Dame, Harvard, Cambridge, Berkeley, São Paulo, Lyon, Montreal, and Tokyo.

|

| Photo # 2 Pope Francis and Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez |

His most influential work, A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation (1971), proposed a theological reflection that unites faith and social commitment, highlighting the “preferential option for the poor,” which became the heart of Liberation Theology and a fundamental principle of Christian action.Would Saint Alphonsus Maria de Liguori (1696–1787), bishop, Doctor of the Church, moral theologian, and great popular missionary, be considered a “communist”? When he founded the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer in 1732, in Naples, Italy, he chose to “evangelize the poor, especially the most abandoned, promoting the abundant redemption offered by Christ.” Isn’t that a preferential option for the poor?

Several saints, such as Mother Teresa of Calcutta and Saint Vincent de Paul, made the preferential option for the poor the core of their ministries.

Saint Francis not only helped the poor — he became one of them. His choice was not to help “from above downward,” but to live among the poor as an equal, imitating the poor and crucified Christ.

“Francis of Assisi was the man of poverty, the man of peace, the man who loves and cares for creation… the man who teaches us to go out of ourselves to find others, especially the poorest,” said Pope Francis, explaining the choice of his name after being elected.

Here are some biblical passages that inspired Liberation Theology:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind, to set the oppressed free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” (Luke 4:18-19)

“Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” (Matthew 25:40)

“For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.” (Matthew 25:35-36)

“Is not this the kind of fasting I have chosen: to loose the chains of injustice [...] to share your food with the hungry...” (Isaiah 58:6-7)

The commitment to the poor is not optional: it is central to following Jesus. Gustavo Gutiérrez wrote: “Liberation theology is a new way of doing theology. It does not start from an abstract reflection, but from the lived practice of faith in the context of poverty and the struggle for justice.”

The preferential option for the poor is a continuation of Christ’s practice, who made the poor and marginalized a priority in his mission. By adopting this option, the Church not only follows Jesus’ example but also responds to the divine call for justice, equity, and salvation for all — especially for those most in need.

The preferential option for the poor arises from the fact that the rich have means to meet their needs — whether for food, housing, medical care, or other necessities — while the poor are often deprived of even the minimum, the essentials to survive. This contrast makes the reality of those who have and those who have not even more unequal. Jesus laments the greed of some rich people, as excessive attachment to material goods prevents them from experiencing true spiritual freedom. He emphasizes that while salvation is possible for everyone, the rich face a great obstacle, since accumulating wealth tends to distance them from God and others.

Jesus explained to his disciples that “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven.” When the disciples expressed surprise at this statement, He insisted even more, pointing out that for those who have wealth, it is extremely difficult to enter the Kingdom of God, because attachment to material things can be a great obstacle. (Matthew 19:23-24, Mark 10:23-25, Luke 18:24-25)

In the book A Life with Karol, written by Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz, personal secretary to John Paul II throughout his pontificate, he recounts that the Pope initially had difficulty understanding the Church’s leftward inclination in Latin America, especially since he had lived under a communist regime.

However, according to the cardinal, the Pope changed his perspective when he had the opportunity to visit the Alagados favela in Bahia and other poor communities in Mexico City. From this experience, John Paul II came to understand the “preferential option for the poor” and recognized that this choice was deeply in harmony with the teachings of the Gospel.

Cardinal Dziwisz also mentions that after this change in vision, the Pope began to refer to the Brazilian Archbishop Hélder Câmara as “my brother.”

Archbishop Dom Hélder Câmara (1909–1999), of Olinda and Recife, once declared: “When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a communist.”

(Hélder, the Dom: A Life That Marked the Course of the Church in Brazil, by Zildo Rocha.2000)

By questioning the structural causes of poverty and people’s indifference toward the needy, he was often labeled a communist. This label served as a way to deflect criticism - especially by those who preferred to ignore the harsh reality of poverty and focus only on themselves.

This quote was recalled by Pope Francis in a speech to the Roman Curia, when he referred to Archbishop Hélder as “that holy Brazilian bishop,” highlighting his commitment to social justice and his option for the most vulnerable.

In 1987, I studied at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. The director of ELOP (English Language & Orientation Program) asked some of us Brazilian students to record a video about the program, which was to be presented at a fair in Rio de Janeiro. When he returned, he invited us to lunch and shared that a priest friend had taken him to visit a favela. His reaction and comments were very similar to those of Pope John Paul II. He said he now understood why leftist ideology had such strong appeal in Latin America.

But it is not a leftist ideology - it is the concrete application of Christ’s message, especially the commandment to love one’s neighbor and the preferential option for the poor.

Part II

When the Devil Gains a Voice: The Breakdown of Friendships and the Moral Collapse of Brazil

I had friends - dear friends. Devout Catholics, people who had prayed more than once in my home, who stood by me during defining moments in my life. We were united by the same faith and religion. Some were personal friends, others virtual acquaintances on social media, with whom I shared a harmonious, affectionate, and respectful relationship. People whom, until recently, I considered part of my closest circle.

But then Brazil saw a figure emerge from the shadows—one who would change everything: the "apostle of the Devil." For now, I won’t mention his name; even the most inattentive reader will know whom I’m talking about.

This man, elected to protect life, allied himself with death and mocked the suffering of families with scorn. He was a denier by choice, driven by his own moral rottenness. He refused to acquire vaccines even when offers were available, deliberately turning down the opportunity to save thousands of lives. He infamously said he “wasn’t a gravedigger” in the face of mass deaths. With cynicism, he made a mockery of other people’s pain.

Inhumane and diabolical: he mimicked, on camera, the gasping agony of people dying from lack of oxygen—grotesquely gesturing, laughing, performing the final moments of those suffocating in overcrowded hospital corridors, while desperate families begged for help. He mocked such suffering, as if death and pain were some kind of joke. He ridiculed masks, scoffed at medical guidelines, and openly discouraged vaccination. He said that “only sissies” would die from Covid-19, and that “real men” weren’t afraid of the virus. This wasn’t ignorance—it was deliberate cruelty. He said it all to provoke, manipulate, and lead people to dismiss the very real danger they faced, even as thousands of avoidable deaths mounted.

An utterly despicable and repugnant individual. He openly claimed that the military dictatorship should have killed over 30,000 people. His declared hero: a torturer and assassin.

While the country grieved, he encouraged mass gatherings—condemned by scientists—walked maskless through crowds, embraced supporters during motorcycle rallies, and used the tragedy as a political stage. He mocked the victims, blamed doctors, attacked science. He said, “Everybody’s going to die someday anyway.” He claimed that anyone who took the vaccine would turn into a crocodile. He told journalists to shut up. He laughed—always laughed—while the dead piled up. Someone like that is not a person. He’s a beast. A vile creature.

- Do you already know who I’m talking about? That’s right. Bingo!

- How do you know it’s him?“Because everything that was said fits him perfectly.”

- Why do I consider him the apostle of the Devil? Because I truly believe he is.

When I think of Bolsonaro, I immediately remember the Italian priest Gabriele Amorth, widely recognized as the Vatican’s most famous exorcist, who passed away in 2016. I see Bolsonaro as one of the real-life characters who could have been treated by him, like those described in his books: The Last Exorcist; Mary, a Yes to God; An Army Against Evil; God is More Beautiful Than the Devil; We Will Be Judged by Love; The Gospel of Mary: The Woman Who Defeated Evil; Begone, Satan!; Investigation on the Devil; The Sign of the Exorcist and Father Gabriele Amorth: The Official Biography.

The exorcist priest recounts many cases and affirms that the Devil doesn’t appear like in the movies, unless provoked by an exorcist. “He’s out there, living inside some people,” he says—and even cites concrete examples.

People!? Is there more than one?

“What is your name?” And he replied: “My name is Legion, for we are many.” (Mark 5:9)

I would love to see Father Gabriele take this man by the hand and ask, as he did with others: “Who’s there?”

It was to him that much of the Catholic right and far-right allied themselves—rough sketches of fascists—though not all of them.

It’s very important to make this clear: not everyone who voted for that man attacked the Church or went on social media calling Pope Francis and Brazilian bishops communists.

For the record: not liking Lula is anyone’s right. But that doesn’t oblige anyone to admire a psychopath.

For three years, while he was still president of Brazil, a friend of mine used to send me messages praising him and attacking Lula. Never, not once, did I talk politics with her. For more than three years, I never commented or contested her almost daily messages because I didn’t want to lose her friendship. But the last straw for me was when she sent me a message claiming that the bishops of the CNBB (National Conference of Bishops of Brazil) were communists. And this, coming from someone who goes to Mass daily, and proudly posts photos on Facebook—then and now—with emeritus and current ecclesiastical authorities from Manaus. Do they have any idea what she said behind their backs?

This, from someone who lost family members to Covid. A diehard denier, she condemned—and still condemns—the use of vaccines. Someone please tell me, for the God's sake: was it the left who discovered the vaccine? The truth is that the son of the father of lies, driven by a morbid desire for more deaths, denied the vaccine—and she, completely disregarding her Christian formation, followed him blindly, as if to say: “We will do whatever the devil commands.”

The same story repeated itself with another friend, who had prayed the rosary several times in my home, with friends and my family. Despite the distance, we often talked via WhatsApp. As a rule, the topic was always something religious. I’ll say it again: we never talked about politics. I was aware of her political stance, always explicit in her Facebook posts.

But just a few hours after Lula won the election against that unhinged man, she sent me a voice message—screaming, and, curiously, just as unhinged. She hurled all sorts of insults at me. My ears are not a sewer.

I distinctly remember her claiming that Lula was a drug trafficker. Well then, she should go to the Public Prosecutor’s Office and report it! I had heard many unprintable adjectives used about him before, but “trafficker” was a new one. She pretends to forget that 86 pounds of cocaine were found on the Brazilian presidential plane in June 2019, during an official trip of President Jair Bolsonaro’s entourage to the G20 summit in Japan.

In angry and hysterical screams—almost in a trance—she was casting curses on Lula, and according to her, it would be none other than Our Lady who would carry them out and return Bolsonaro to power. She spoke as if Divine Justice were about to take the stage, dressed in a heavenly robe, to restore to the throne that morally despicable man.

I heard nonsense after nonsense, in such an absurd sequence that the only thing missing was the soundtrack of the Apocalypse. And there I was, in silence, wondering: what fault is mine, if I didn’t even vote in Portugal?

That’s when she began her personal crusade against part of the Church. Since then, she has been practically on a divine mission: attacking on social media every single member of the Church who hasn’t surrendered to her political-messianic project. A true influencer of selective faith.

Dreaming of a civil war—deaths, more deaths, and even more deaths!—Bolsonaro nurtured the desire to see all his followers armed to the teeth. He advocated the unrestricted release of weapons to “good people,” meaning those who think and act exactly like him.

On October 12, 2021, during the solemn mass in celebration of the feast of Our Lady of Aparecida, Archbishop Orlando Brandes made a strong and emphatic criticism of the release of weapons to the so-called ‘good people’ defended by Bolsonaro, ironically invoking the government's slogan "Beloved Homeland".

In his sermon, Archbishop Orlando stated categorically: “To be a beloved [amada] homeland, [as our national anthem says], it cannot be an armed [armada] homeland.”

Another friend, inseparable from the one mentioned earlier, posted a Facebook message criticizing the archbishop and added that “this will not be forgotten.” In other words, God would not forget to punish the archbishop for his boldness.

These are just three examples—and they’re far from isolated cases. I have a veritable encyclopedia on this: on the behavior of the Catholic right and far-right, which have allied themselves with reactionary sectors of the Church to attack bishops and Pope Francis—with astounding aggression.

No one can take this credit away from the Son of the Devil: thanks to him, a lot of so-called “good people” came out of the closet. They were wolves in sheep’s clothing. He is responsible for the rise of the “Phariseeminions” — individuals who display a religious or moralistic posture (like the Pharisees), but are also fervent and uncritical followers of former president Jair Bolsonaro, also known as Bolsominions. In other words, a “Phariseeminion” is someone who presents themselves as a defender of morality, Christian faith, and “traditional values,” but acts with hypocrisy, intolerance, or hateful rhetoric — often supporting aggressive, anti-democratic, or unethical political stances, which contradict the very Christian values they claim to uphold.

Thousands became enraged with the Church because it didn’t support the authoritarian and far-right Brazilian candidate. As absurd as it sounds—something surreal—they see in his second name, "Messias" (Messiah), not a mere coincidence: they believe they are in the presence of a defender of morality and good customs, regardless of what he said or did.

Before continuing and revealing who feeds this group with reactionary ideas and attacks on the Pope and bishops—widely disseminated on social media—it’s necessary to clarify something.

As we’ve seen, many Catholics became outraged with the Church for political reasons. Among them, some found refuge in reactionary groups and began to echo their ideas.

These groups, although politically motivated, primarily attack the Pope for religious reasons: because they oppose the Second Vatican Council, argue that Mass should be celebrated exclusively in Latin, among other positions we’ll explore shortly.

To introduce Brazil’s main reactionary group, I need to tell a short story.

Earlier, I mentioned that I asked an “acquaintance” what she thought of the new Pope. This time, I asked a question to a woman I didn’t know, who attends one of the churches where I usually go to Mass.

I noticed that, when receiving Communion, she kneels and takes the host on the tongue. Both the priest and the deacon are present at the celebration—but she never receives Communion from the deacon.

Typical behavior of the new Pharisees.

I know this profile well: almost saintly. But I avoided jumping to conclusions—not everyone who receives Communion that way attacks the Pope. However, many who do take that approach claim—and post—that Pope Francis is a communist.

I approached her and started a conversation:

— You're Brazilian, right?

She confirmed. I already knew. I had heard her speaking Brazilian Portuguese. So I moved to the second question:

— What do you think of the new Pope?

She said she liked him. So I went for the third question—really the one I was aiming for:

— And what do you think of Pope Francis?

She said she liked him, although she didn’t agree with everything. She pointedly asked me if I had read the encyclical Fratelli Tutti. She seemed quite opposed to it.

I wasn’t bothered by the question—in fact, I was glad I approached her, and even glad I was wrong about her—because I avoided making an unfair judgment.

When we were already outside the church, she called me and asked why I had asked those questions.

I replied that the way she received Communion reminded me of people who do the same and often call the Pope a communist—I told her I noticed that wasn’t her case, and I made that clear.

I added that I know some people who receive Communion that way and who like to criticize the Church—“Narcissus finds ugly what isn’t a mirror.” Specifically, I mentioned one who frequently criticizes the Lenten Fraternity Campaign and spreads videos of priests who invent doctrines that add nothing to the Gospels nor lead to salvation. I told her that, in my view, following those teachings doesn’t guarantee heaven, just as not following them doesn’t lead to hell.

I mentioned that one of those people had posted a video of a priest forbidding us to open our arms during the Our Father. According to him, that gesture represented the crucified Christ and, for that reason, we should pray with hands joined.

I said that this kind of behavior, in its superficiality, can be described as Pharisaical, as it reveals a morality that favors appearances and external rituals over truly transformative and charitable actions.

The idea that simply attending Mass every day, making pilgrimages to shrines, or considering oneself “good” because of religious practices—without real commitment to social justice—reflects a posture that ignores deeper human needs.

“But someone will say: You have faith, and I have works; show me your faith without your works, and I will show you my faith by my works.” (James 2:18)

Not rarely, this type of religiosity aligns itself with authoritarian and oppressive regimes, which seek to control and manipulate faith to justify power and exclusion.

She interrupted me with long and harsh criticisms of this year’s Lenten Campaign.

And then she dropped this gem:

— The CNBB does not represent the Brazilian Church. The CNBB is just a bishop’s organization.

For the record: the themes of the Lenten Campaign each year are chosen by the CNBB itself.

She also criticized the Fratelli Tutti encyclical and said I should get more informed. She suggested I check out the Centro Dom Bosco's website.

When I heard that, I felt a shiver all over my body. We debated for about fifteen minutes. Every other sentence, she repeated that I was “clueless” and needed to consult the Centro Dom Bosco “to be properly catechized”—not in those exact words, but the subtext was clear.

Stunned, the only thing I managed to ask was: Are you referring, by any chance, to that center frequented by the actress Cássia Kiss, known for her defense of religious fundamentalism and alignment with political authoritarianism?

That shiver came precisely because I know exactly what the Centro Dom Bosco is—and I also know it has no relation to the Salesian Congregation.

It’s necessary to explain to the reader what the Centro Dom Bosco (https://www.centrodombosco.org/) is, and especially for Portuguese readers, to contextualize what the Lenten Campaign is, and why so many Catholics who call the Pope a communist hate it.

The Fraternity Campaign (Campanha da Fraternidade), started in 1964, is an annual initiative of the CNBB (National Conference of Bishops of Brazil) that proposes a theme related to Christian faith and the country’s social reality, encouraging reflection, conversion, and concrete action during Lent.

In 2025, the theme was “Fraternity and Integral Ecology” and the motto was “God saw that it was all very good” (Gen 1:31).

Inspired by the 800th anniversary of St. Francis of Assisi’s Canticle of the Creatures, the 10th anniversary of Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato Si’, and the upcoming COP 30 (UN Climate Change Conference) in Belém, Brazil, this year’s campaign invites ecological conversion and care for God’s creation. Far-right Catholic groups such as the Centro Dom Bosco and Confraria Dom Vital criticized this year’s campaign. They argue that it promotes an “ideological agenda” aligned with secular environmentalism and globalism, distancing itself from traditional Catholic doctrine.

Who are these groups?

When I lived with my family in Canada, in 2012, we were visited by two young Mormon women from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I let them in and allowed them to speak freely before challenging anything. They told us that Joseph Smith, founder of their church, had received the mission to restore the true Church of Jesus Christ. In essence, this same claim underlies the actions of these far-right Catholic centers: the idea of restoring—in their way—what they consider to be the true faith or true order.

I've already commented on other reactionary Catholic groups, such as the Heralds of the Gospel (https://www.arautos.org/) and Tradition, Family and Property (TFP).

The Centro Dom Bosco is composed of traditionalist lay Catholics who stand out on social media for their aggressive rhetoric against Pope Francis, the CNBB, and documents such as Laudato Si’ and Fratelli Tutti. They claim to represent the “true faith” and promote a narrow vision of Catholicism, marked by a supposed orthodoxy that rejects the reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

The Confraria Dom Vital (https://centrodomvital.com.br) operates in a similar way, promoting ultra-conservative content and encouraging boycotts of the Lenten Campaign. Both groups advocate a return to the Tridentine Mass (in Latin, with the priest facing away from the congregation), scorn the use of vernacular languages in the liturgy, and cling to external forms of piety—as if visible gestures and postures could guarantee salvation, regardless of one’s commitment to justice, charity, and living the Gospel.

Both groups foster a Pharisaical religiosity focused on rules and appearances, and politically align with the far right, promoting disobedience to the Church's Magisterium and hostility toward any openness to dialogue with the contemporary world.

They criticized Pope Francis when he defended the rights of the marginalized, migrants, or denounced the economic causes of poverty. In their discourse, they romanticize suffering, exalt resignation, and reject any critique of the system that creates inequality.

This stance not only strays from Christianity’s most humanistic principles, but also helps sustain a political and social system that disregards the poor and vulnerable. The focus on empty rituals, without commitment to necessary societal changes, turns faith into an instrument of control and oppression, rather than a force for liberation and equality.

Here in Portugal, I know a man—a Eucharistic minister who goes to Mass every day—who posted, in a WhatsApp group where he advocated for my expulsion, a photo of a Black family—barefoot parents and children, possibly immigrants—and wrote: “Portugal doesn’t deserve this.” Would he react the same way if it were a blue-eyed Ukrainian family?

This is clearly a racist attitude and a deep contempt for the poor. It is the image of a distorted faith: he prays, receives Communion, serves at the altar—but rejects and dehumanizes those with whom Christ most identified. Jesus said: “Whatever you did for the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” (Mt 25:40). This contradiction between religious practice and exclusion reveals a facade of Christianity—the kind Jesus most condemned: a whitewashed tomb.

I found it sad, but not surprising. From the messages he usually posts, he’s just another widow of the Salazar dictatorship in Portugal—a typical representative of far-right Catholicism.

To be fair: the parish priest of the church where this man serves always asks for respect and consideration whenever his homilies address immigrants. He never forgets that millions of Portuguese people also emigrated to other countries.

“He replied, ‘Isaiah was right when he prophesied about you hypocrites; as it is written: This people honors me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me.’”(Mark 7:6)

|

| Photo #3. Fake message from the Pope. Translation below |

Far-right Catholics and fascists share compatible DNA.

In many cases, the behavior of far-right Catholics closely resembles fascist behavior, as described by Jason Stanley in his book How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. The adherence to a superficial morality, focused on appearances and external rituals rather than concrete actions of social transformation, is one of the core features of authoritarian regimes. Stanley argues that by creating divisions between “us” (the morally pure) and “them” (the enemies or marginalized), fascism manipulates faith and religious symbols to consolidate power. Likewise, sectors of religious conservatism often cling to a punitive and rigid moralism, ignoring deeper social needs and resisting structural changes that promote equality. This stance not only distorts Christian teachings but also reinforces the perpetuation of an unequal political and social system—thus echoing the practices of fascist control and oppression.

With the advent of the new Pope Leo XIV, everything changed. Happy to be rid of Pope Francis, the new Pharisees are already spreading false quotes, attributing to him words that fit their own narratives. Fake videos with speeches by the new Pope are circulating. I’ve already seen two. The goal is clear: to erase Pope Francis’s memory and reshape Leo XIV into their own image and likeness—to sell the Pope of their dreams.

I hate to spoil the party, but in the Diocese of Chiclayo, Peru, where Bishop Roberto Prevost once served, there were Base Ecclesial Communities (CEBs), as in many regions of Latin America—especially where the Catholic Church maintains strong social and pastoral work with the poor.

Originating in Latin America, with decisive momentum in Brazil, the Base Ecclesial Communities (CEBs) consist of small groups of Christians, mostly Catholics, who meet regularly to reflect on the Scriptures, live out their faith in community, and discuss issues relevant to their local reality, always in the light of the Gospel. Their emergence was strongly influenced by the Second Vatican Council and Liberation Theology.

In Peru, the CEBs have played a significant role since the 1970s. Despite resistance from more conservative sectors of the Church, they have continued to express a faith committed to the lives and struggles of the poor.

It’s worth noting that Bishop Roberto Prevost was also part of the leadership of Caritas Peru — a Catholic organization dedicated to human development and serving those in need, with a strong presence among grassroots communities. This highlights his direct involvement with pastoral practices aligned with popular movements and the Church of the poor.

I’m starting to think that Pope Leo XIV has communist roots. Thank God.

This Sunday, Pope Leo XIV "took office" with a public Mass in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican. In his homily, the Pope emphasized the importance of faith in times of uncertainty and said he will lead the Church with “courage, clarity, and charity.”

We are left to acknowledge the mystery that surrounds every papal election: “The Spirit blows where it wills” (John 3:8) — and thus Leo XIV was chosen.

Cláudio Nogueira

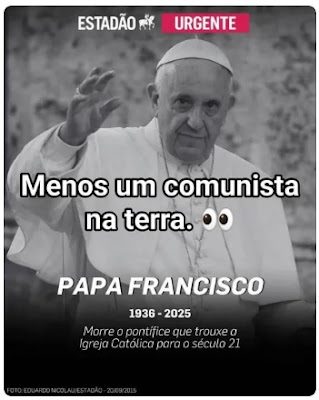

PS1. Photo #1 is real. It was published by the newspaper O Estado de São Paulo, nicknamed Estadão. It reported the death of Pope Francis. The photo was used by haters who wrote on it: "One less communist on Earth" and shared it on social media. Several similar messages were posted on social networks.

PS2. Photo #3 contains a fabricated quote falsely attributed to the newly elected Pope. The message, which states "Communism has even penetrated Christian circles, disguised as solidarity. It is our pastoral duty to expose it," has been circulated on social media by certain Catholic groups seeking to project their own ideological views onto Pope Leo XIV.

PS3. As always, the far right is spreading lies by posting fake messages attributed to the new Pope. And this is just the beginning. In this fake video, titled: 'Pope Leo XIV shocks the world by mentioning Bolsonaro in a historic speech | see what he said...' (Content in Portuguese), the disinformation continues.

PS4. Steve Bannon is a former banker and media executive, known for his central role in the rise of right-wing populism in the United States and other parts of the world. He gained notoriety for his strong ties to Donald Trump, having served as the chief executive of the 2016 presidential campaign. Bannon was White House Chief Strategist and Senior Counselor to President Trump from January to August 2017. That same year, he broke with the White House following controversial remarks about the president's family, published in a book. He currently holds no government position.

He is considered a key ideological influence on Bolsonaro's sons, particularly Congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, who frequently visits or publicly references him. (Click the link to watch the video)

Bannon predicts Robert Francis Prevost will be elected Pope

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário